Training Distance Runners

At the start of a new training regime, the main goal of training is to increase aerobic capacity (endurance), improve the metabolic energy system functions and develop the musculoskeletal system to endure the physical stress of running. Anaerobic training should also be introduced at the program's start with hill running, strides, and basic sprint drills to improve running mechanics.

Training Elements

All elements of training are included during every cycle, with a different emphasis during each period. Maintaining or improving both aerobic and anaerobic abilities during every training cycle in the program will be beneficial to develop all the qualities needed for championship competition.

Training starts with speed development and longer endurance workouts, gradually building to more event specific speed and endurance until the championship phase. Programs are designed to be a continuous build up with the speed and endurance elements to the most specific training features as the championship phase of the season nears.

Intertwining aerobic and anaerobic abilities in the training program will require changes in pace, recovery, volume, and intensity based on the needs of the athlete and event demands. Starting the training program with slower aerobic pace running and speed development will provide the foundation for all the qualities needed to maximize performance when it matters most.

Aerobic Foundation

Continuous easy running with a heart rate at or below 130 beats per minute is considered low intensity exercise. Easy running is often used to build the aerobic foundation with general endurance training and recovery work between more intense sessions. Workloads at lower intensities will improve the capacity of the runner to supply oxygen to the muscles using oxidative phosphorylation.

Aerobic Intensity

“The prescription of running intensity during prolonged workouts has always been an approximate endeavor” (Karp, 2001 p. 5035), in part due to the perceived effort of the athlete and the less than practical scientific measurement systems available to most coaches to test Vo2Max and blood lactate levels. Heart rate is an easy physiological measurement to indicate intensity that is reliable and objective to evaluate intensity.

Measuring heart rate is a great way to measure the intensity of exercise and improvements in aerobic fitness. There are scientific methods to measure VO2Max and lactate; however, heart rate is the simplest and most practical tool for most athletes.

Heart rate is used as an indicator for the intensity of effort in training. Heart rates from 130-170 beats per minute will develop an aerobic base for endurance events (USATF, 2015). Heart rate can measure intensity and progress during the season. Maximum heart rate can be estimated by subtracting an athlete’s age from 220.

Training below 100% of VO2Max using continuous running and interval training is considered aerobic training.

Training Sequencing

Proper training for endurance events includes aerobic and anaerobic methods. The pace and duration of aerobic and anaerobic sessions vary based on the type of training system and the athlete's individual needs. Using both aerobic and anaerobic elements during each training cycle has been successfully implemented in various periodization models.

Linear periodization in endurance events starts with low intensity and high volume training with a gradual reduction in volume as intensity increases. With linear periodization, aerobic capacity is established, followed by higher intensity aerobic training for power. Anaerobic capacity is developed after higher intensity aerobic training. The focus on anaerobic power training is included after anaerobic capacity.

Mixed periodization in distance running begins with less specific training methods for endurance and speed and gradually progresses toward event specific training. In mixed periodization, training starts with pacing well below the competition event pace for endurance sessions and above the competition event pace for speed sessions. After the first training cycle, the training volume is constant until the peak phase (Magness, 2014).

Regardless of the periodization methods, aerobic capacity is the foundation for all endurance training programs; aerobic endurance will help maintain the foundation throughout the entire season. Endurance and speed based training methods must be part of every cycle to maximize performance fully.

The top runners train to increase available energy in both aerobic and anaerobic energy systems. Mixing in the correct type of training at the right time is one of the significant challenges to coaches; however, good record keeping, proper feedback, and constant training evaluation will help the coach and athlete optimize performance.

Coaching Note: anaerobic training for long distance runners is usually 10 to 20% of total training volume and 25 to 40% of training volume for middle distance runners. The amount of anaerobic training should reflect the approximate percentage of anaerobic energy needed for the competition event.

Season Design

Create a competition schedule and highlight events for peak performance

Develop a plan based on the adaptations needed for the goal performances

Build the plan backward from the last competition to the first day of training

Divide the program into phases or cycles with benchmarks to show progress

Use individualized training with specific goals for practice and competition

Discuss training targets frequently and make adjustments as needed

Be open to contingency plans based on the physical and mental state

Periodization

Preparation Phase

Theme: Duration Not Intensity

Endurance

- Start with easy runs and aerobic threshold runs

- Slowly increase the duration (5-7 minutes longer each week)

- Progression runs to build intensity slowly

- Add lactate threshold training after 3-4 weeks

Speed

- Resisted pure speed and speed endurance (hill running)

- Strides after easy running

Workout Frequency and Types

x4-5 sessions of easy running to aerobic threshold running, including a long run

x1-2 sessions of fartlek running up to lactate threshold pace for short burst

x1-2 sessions of speed using set/reps (general speed, resisted speed, and/or strides)

Preparation Phase Guidelines

- Focus on duration, not intensity

- Progressively increase mileage during the season until the peak phase

- Train speed with strides and hills

- Include progression runs to add speed to distance runs

Coaching Note: the aerobic foundation developed in the general preparation phase will allow for more specific faster endurance training in later training cycles.

Pre-Competition Phase

Theme: Balance Intensity and Duration

Endurance

- Maintain long easy runs for aerobic capacity

- Add more intensity to continuous running sessions

- Introduce event specific endurance (-/+ two paces)

Speed

- Introduce event specific speed (-/+ two paces)

- Add interval training to replace sets and repetitions

- Add mixed speed methods

- Strides after easy running

Workout Frequency and Types

x3-5 sessions of easy running to aerobic threshold pace including long run

x1 session of fartlek or progression running up to lactate threshold pace

x1 session of event specific endurance intervals

x1 session of speed intervals (mixed speed, event specific speed, and/or strides)

x1-2 sessions of blended speed and endurance workouts

Pre-Competition Guidelines

- Decrease general endurance training

- Long easy runs to maintain aerobic (every 10-14 days)

- Increase intensity of endurance based training

- Blend speed and endurance in the same session

- Add length to speed workouts

Coaching Note: more intense work segments and recovery periods are closer in pace as the season progresses.

Competition Phase

Theme: Specific Event Preparation

Endurance

- Event specific endurance (-/+ one pace)

- Add competition event goal pacing in workouts

- Use mixed speed methods that are specific to the competitive event

- Lower general endurance mileage

Speed

- Event specific speed (-/+ one pace)

- Add competition event goal pacing in workouts

- Use mixed speed methods that are specific to the competitive event

- Strides after easy running

Workout Frequency and Types

x3 sessions of easy running

x2 sessions of aerobic threshold pace or progression run

x1 session of event specific endurance intervals

x1 session of speed intervals (mixed speed, event specific speed, and/or strides)

Competition Phase Guidelines

- Increase in intensity in endurance training

- Decrease volume of endurance training

- Complete recovery between intense training sessions

- Train at or above event specific goal pace

- Blend faster paces for longer durations with speed and endurance sessions

Coaching Note: keep easy and hard days easy; higher intensity workouts require more recovery between sessions, typically 48-72 hours.

Peak Training

To peak, allow more recovery between intense training sessions and a slight drop off in volume. Dramatic changes in the training plan can have adverse effects; peaking should be part science and part art, based on experience with each athlete. Experimenting with volume and intensity to the peak is best done earlier in the training program to test the athlete's reaction to specific training methods.

Training can have predictable outcomes, but it can vary within each athlete; the same training dose given during different times of the year could illicit an unintended response; therefore, repeated testing and monitoring are necessary. With minimal trial and error, peak performance can be refined and be more predictable with proper data gathering.

Training Design Tips

- Combine speed and endurance in all training cycles

- Speed training progresses to be more event specific by adding length

- Endurance training progresses to be more event specific by reducing the length

- Training emphasis is based on the qualities needed to maximize performance

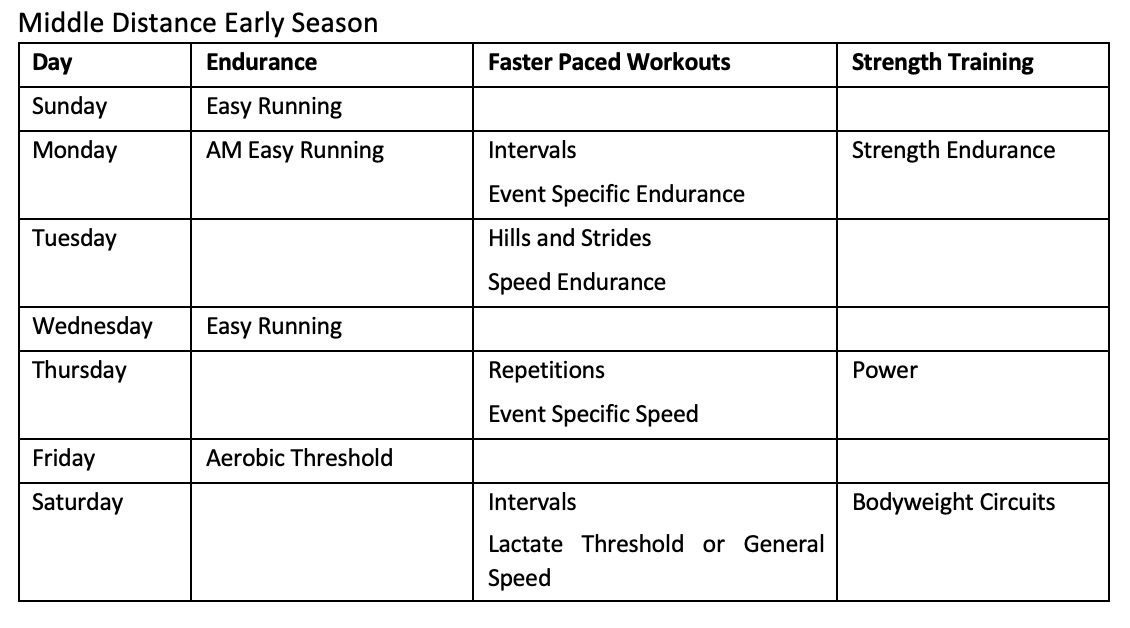

Sample Training Middle Distance Runners

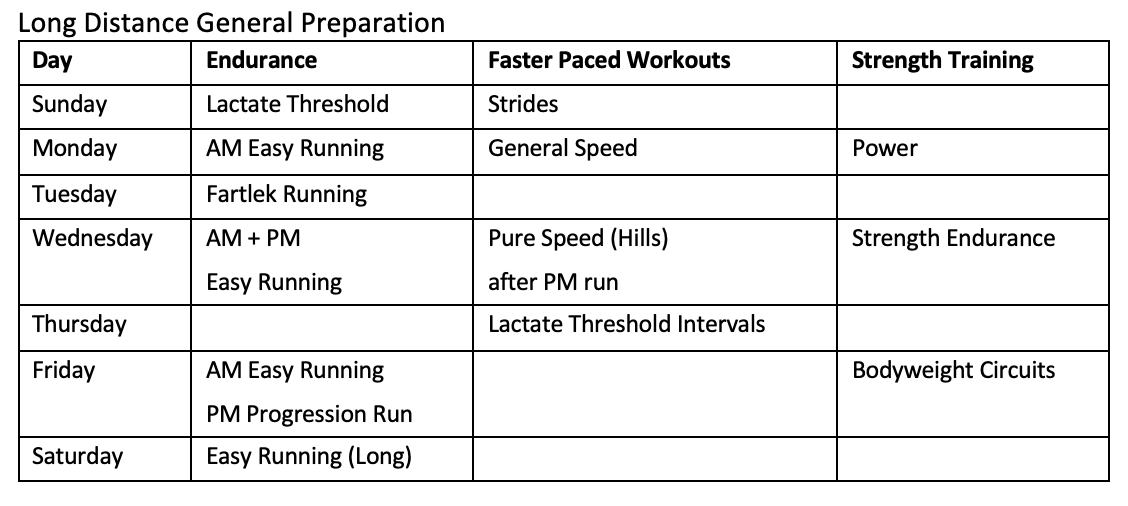

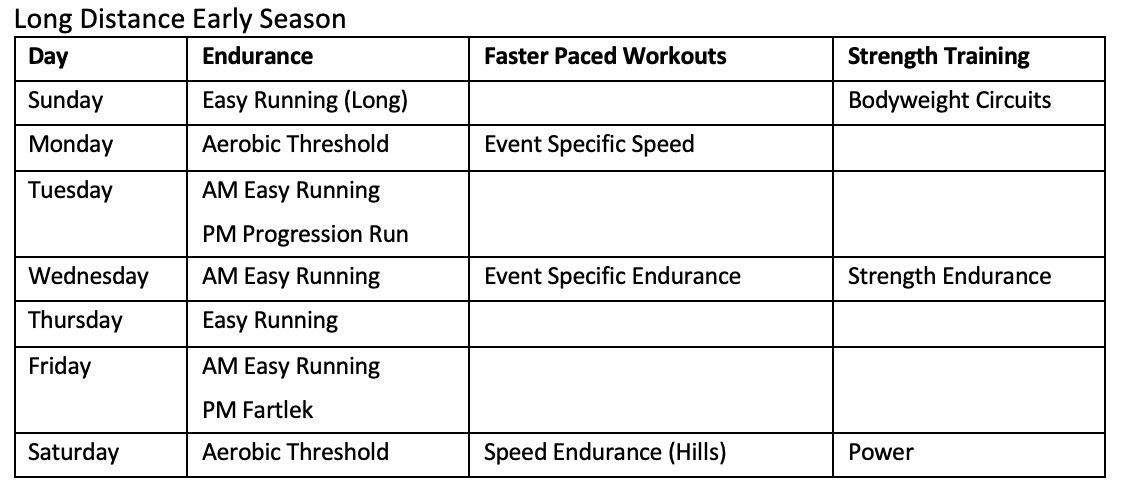

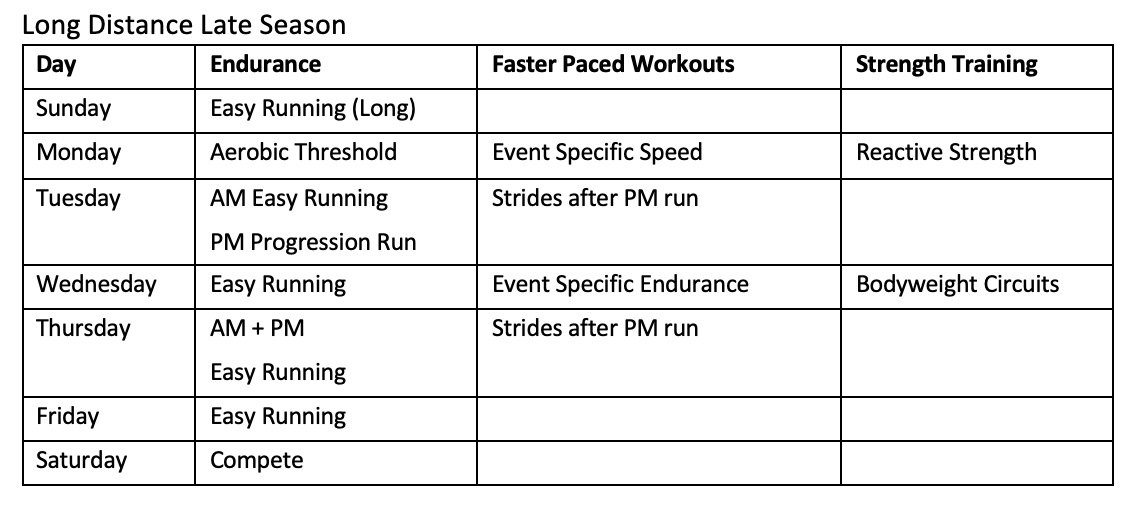

Sample Training Long Distance Runners

Cross Country

Developing a cross country program at the high school level requires careful attention since governing bodies in most states limits preseason activities for a season that is invariably shorter than that of other high school sports. Books dealing with the training of world class athletes are less than helpful, not only because of the vast physical differences but mainly due to the limited time frame given to the high school cross country coach.

While a well established program may have the athletes training in groups during the summer, many coaches are faced with a group of poorly conditioned cross country hopefuls.

The great New Zealand coach Arthur Lydiard would have his elite athletes run long runs over various terrains for at least ten weeks (about the length of a high school season) to get them prepared for what he would call 'training'. He felt that the key to cross country progress is aerobic capacity. When we were fortunate enough to get the opportunity to spend several hours alone with Lydiard a month or so before he died, we discussed this philosophy as it concerned high school athletes.

He was adamant that putting in the miles is the key to success. These runs are generally done at "talking pace," which is a speed that increases as fitness increases. This long distance training forms a base upon which the real training program can be built. Opponents cry out that runners cannot learn to run fast by running slowly, but the base is merely a conditioning process to prepare the entire body to be able to handle a very intense work load.

Some coaches go wrong because they will see measurable increases in speed with the endurance phase and, therefore, neglect the faster tempo and speed work necessary to gain optimum performances for the championship races.

Then, an essential ingredient in building a successful high school cross country team is a summer training program. In some states, coaches can be directly involved, while they must have no contact at all in others.

Team captains can conduct summer runs. This takes the coach out of the equation and helps develop a sense of camaraderie and team unity. In most programs the athletes meet at a chosen location three to five days a week and then split into groups based on ability.

The runners set out on their respective courses for a given number of miles or minutes. For developing a sense of "team," choosing minutes works out better as everyone finishes at the same time no matter how far they have run. Finishing at the same time allows runners of all abilities to do the stretching and core strength exercises as a unit.

To reach the highest levels, top high school runners usually log between 50 and 90 miles a week during the off season with less mileage run during the weeks of higher intensity training. These athletes add mileage each year to their weekly totals.

Most freshmen aren't prepared to handle the same mileage as a senior, especially when the intensity increases. Most programs continue to include a long run each week to help maintain aerobic development. Many of the top high school programs also include an easy team run before school each morning.

Ideally, the coach greets a group of youngsters who are fit and ready to go after training throughout the summer. Realistically, many still fall far from this category. These kids need a bit of fairly easy distance running to prepare their systems (muscles, tendons, lungs, heart, and self confidence) for competitive training.

For some kids, that means most of the season will involve getting ready to start training. For the better prepared, faster workouts will be started almost immediately. It is essential, though, that high school runners build as strong a base as possible before high intensity runs.

What happens when the regular season begins varies tremendously among the top programs. Some have succeeded with high mileage programs (this term includes distances from 50 miles per week to well over 100). Others emphasize fast runs, and still, others base their workouts on a very small amount of running, emphasizing a series of drills.

Fortunately, there are a large variety of activities available to steer your athletes toward success. Physical fitness can be improved in more ways than simply running. Core strength can be increased through specific exercises. Various drills can improve neuromotor skills, correct stretching exercises can increase stride length, and specific running drills can increase stride rate and efficiency.

During the cross country season, a coach can use a variety of workouts to help improve anaerobic fitness and prepare the runners for races. These workouts (examples listed below), such as mile repeats, kilometer repeats, Oregon drills, and sharpening speed, give coaches plenty of different options for helping the athletes peak at the highest level at the right time. Athletes, typically, should start the season with longer repeats which add up to a bit more than the distance of the athlete’s race (5,000 meters for most states), and run each interval at date pace (level of the athlete at the current time) or just below goal pace.

During the middle of the season, as the team approaches conference championships, athletes are running intervals that add up to race distance and are at race pace or goal pace per repeat. During the peaking stage, the athletes will be running repeats faster than the goal pace in a shorter overall length than the race itself.

Areas often overlooked in coaching high school distance runners have nothing to do with workouts, drills, or exercises. The most important intangible for high level success is "expectations." No matter what the sport, the coaches who produce championship teams every year are those who truly "expect" their athletes to succeed.

While some are hoping to place high in their respective league championships, the kids in the top programs are certain that they have a chance to win the state or national championship.

Former Mead High School (Spokane, WA) coach Pat Tyson always started the cross country season with the statement, “We are going to be state champions this fall.” That actually happened 16 times during his 23 years at Mead. Expecting to win was the key.

Another non-running key to success is for the coach to ensure that all team members feel important. The best athletes in all sports gain the most recognition, but cross country is a unique sport where the slowest runner may never outrun anyone, yet that runner can work hard and at the least improve.

A good coach will note kids with these improvements and create a team with all sorts of winners.

High School Distance Running Training

Examples of Running Workouts and Drills

Mile Repeats: Mile repeats can be done on the track, at a golf course or on a maintained trail. Take 2-3 minutes rest in between each mile repeat. Start each season by doing 4 or 5 one mile repeats. Decrease to three repeats as the pace gets closer to race pace. End the season with a mile time trial.

Oregon Drills: Using the perimeter of the football field, stride the length at an easy pace (let’s say 10,000 meter pace to half marathon pace). Then cross at the goal post, jogging to the other side. Run the length at a medium stride (5k pace or cross country pace). The athlete will again cross at the goal post and then run the length at mile race pace. The athlete will repeat (easy, medium, hard) for 30-40 minutes in the early season and down to 15-20 minutes during the late season. This drill is a good one to two days before a hard invite or a championship meet. Athletes may run these barefoot (massages the feet and improves ankle strength) or in racing flats (good time to break in new racing shoes). Likewise, this workout works well when the athletes are tired.

1k / 200 meter repeats: The one kilometer / 200 meter workout is a great workout for alternating race pace with hard anaerobic running. The athlete runs a 1k at race or goal pace followed by an immediate 200 meter jog. Then the athlete goes straight into an all-out 200. Take 2-3 minutes to rest after each set. 6-8 sets are usually done at the start of each season and get as low as 2-3 sets at the end of the season when the kilometer is run at race pace or faster.

1600 meter drill: Place a cone at every 100 meters on a track. Run a hard 500 followed by an immediate 400 jog, a hard 400, jog 300, a hard 300, jog 200, a hard 200, jog 100, a hard 100, jog 100, hard 100. This system continues nonstop throughout the workout. All the hard work adds up to 1600 meters. This workout is best done the Tuesday before a major race. Complete each set (1600 meters) three times with no rest between each. Run at 5k date pace during the early season and gradually increase the tempo until it is faster than 5k goal pace at the end of the season.

Drills/Circuit Training:

The main thing one should do in drills/circuit training is to build up and develop the central nervous system by doing a series of dynamic movements. We call this neural training. Neural training is designed to enhance running specific strength and coordination workout muscles that are controlled by the central nervous system. These drills may include the following: Skipping, Skipping backward, skipping with crossing arms, lateral skips, high knees, butt kicks, horse kicks, hamstring skips, skipping for distance, ABC’s, walking high knees and more. Other drills are useful such as tempo quick skip, speed running (in place) and hip flexor swings. Calf raises, walking lunges, side to side lunges, and vertical hops are also used. These drills are used on a daily basis.

“4 sets of 3”

The four sets of three drills are used to decrease the chances of runner’s knee, IT band problems, ankle issues, hip flexor problems, and shin splints. The athletes set cones 75 meters apart before they begin the drills. They will then do four sets of movements [1. walking, 2. skipping, 3. running, and 4. hopping]. For each mode, there will be 75 meters with the toes straight, 75 with the toes facing inward, and 75 with the toes facing outward. Do all three styles with walking and then proceed in the same order with skipping, running, and hopping. Athletes must make sure they are over-exaggerating the movements in these drills. All the movements used in these drills work every muscle from the lower central nervous system to the athlete’s feet. This drill is done every day BEFORE practice and is performed seven days a week!

Examples of High School training weeks: (Athletes should, in addition, have a good warm up, drills, and stretching before each workout and a warm down and stretching after). W in the schedule stands for days to do weight training.

Sample High School XC Training Week

Monday: Easy 60-70 minutes with drills and strides

Tuesday: 4-5 x 1600 at date pace or slightly slower than race pace

Wednesday: Easy 60 minutes with drills and strides

Thursday: Oregon Drills

Friday: Easy 50 minutes with drills and strides

Saturday: Race or Time Trial

Sunday: Long Run – up to 3 hours. Finish up the long run with 12 x 110 meter grass strides.

Sample High School XC Conference Training Week

Monday: Easy 50-60 minutes with drills and strides

Tuesday: 5 x 1k/200. 1k at date or race pace with a 200 meter jog after followed by a 200 all out. Rest 2 minutes and repeat.

Wednesday: Easy 50 minutes with drills and strides

Thursday: Oregon Drills (30 minutes total) + 16 x 110 meters runs at mile race pace

Friday: Easy 40 minutes with drills and strides

Saturday: Race

Sunday: Long Run – up to 2 hours. Finish up the long run with 12 x 110 meter grass strides.

Sample High School XC State/Post Season Training Week

Monday: Easy 40 minutes with drills and strides

Tuesday: Time Trial 1600 meters followed by team relays. Athletes break up into teams of two and run 300 meter trade off relays. Each athlete doing 5 to 8 each OR 3 sets of the 1600 meter drill.

Wednesday: Easy 40 minutes with drills and strides

Thursday: Oregon Drills – 15 minutes

Friday: Course Run with drills and 8 x 110 strides

Saturday: Championship Race

Sunday: Long, Easy Run